Author: Ivan Gulmesoff

Spring/Summer 2021

Select excerpt from July 2021: SHIELDWatch Newsletter

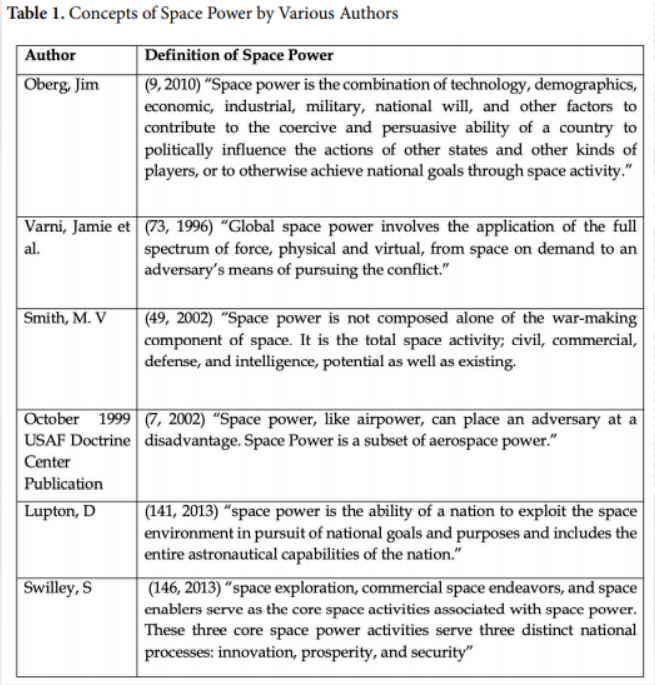

This article outlines the necessity of an accurate framework for US space operations, starting with the 2001 Rumsfeld Commission’s initial recommendations, including establishing a military space department. The US Space Force was established as an independent command in 2019, but we have yet to centralize our space infrastructure across private and public sectors. In this article, Gulmesoff lays out how our definition of space power influences our security and infrastructure for space-based logistical measures.

As part of building a space industry, defining the way risk is evaluated will ultimately help to mitigate it. One example of the challenges to maintaining our security as we build out our space program is the interconnected civilian-military satellite communication infrastructure and the benefits and vulnerabilities it creates.